Two-Slice Software Teams

15 December 2018 ~ 4 min read ~ Engineering, Leadership, Startups

Amazon’s Two-Pizza-Teams is a scaling methodology that suggests organizational designers ensure independence and speed by keeping ownership of products to teams that can be fed by no more than two pizzas. These teams need total decision-making authority of their product, and a clear understanding of what success means for them. This works well for Amazon as these small teams behave as composable units of opportunity and service for customers internal and external.

Two pizza teams are about eight people, plus or minus two. That’s a great size to have a mix of analysts, engineers, quality and success folks. This article is about a bad habit I’ve had in building products under the direct care of only one person, usually an engineer; a two-slice team.

It starts innocently enough

In building consumer software, research and development need to be two different things. I’ve been guilty too many times of assigning a single engineer to do some exploratory development on a new product or sizeable feature, and then not reinforcing their efforts enough as the research leaves the lab.

The story goes like this: there’s a new platform we want to install some technology into. A fearless and talented developer dives in and by Friday she has a deceptively slick looking proof of concept of the main workflow. There’re some obviously rough edges, so, sure, why not keep going until the demo is like butter. By this time the engineer’s started an expanding list of //TODOs that are really more critical than they are nice-to-have.

Without stopping, a few weeks later, this prototype is being talked about like it’s customer-ready software. Pretty soon marketing and customer success are being spun up to trumpet about this achievement to your customer base, and before you know it this research product has paying customers, problems, and is going to need love and support for years.

That was fast

What I just described isn’t necessarily indefensible. There are times when you want to parachute in and make something available in short order. Just do it sparingly. Don’t make a habit of having hero-engineers launching half-mature hit after hit without stopping to take stock.

At about the second week of an exploratory project it’s time to stop and take stock of what the future of this line of development is really going to take:

- What are the six hacks that made this look more robust than it really is?

- What’s weird or unique about this new environment that we don’t really understand yet?

- What parts of this are going to need some automated tests and deeper QA?

- Now that we have a sense of this thing, what should we adjust about the original plan?

- How much ongoing time are we going to need to feed this project after v1 is out the door?

- Is this MVP a minimally loveable product?

Take stock of these concerns now. Do with them what you will, but at least have the estimates and information.

Too lean too long

“If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.” – Unknown

This lesson is about portfolio management. After a few months carrying all the water for this product, this person is going to be burning out. The problems they’re struggling with are going to be taking on a character of insurmountability. The project needs fresh eyes and diversity of thought. You’ve got to either staff up a team around this project, or fold the project and the engineer into another group that can afford to lend a hand.

How many of these major features/projects exist for your team? How many exist whose engineer has been reassigned, likely repeatedly?

Automation is the aim in software, so to some degree it’s desireable to have bits that’re trustworthy and haven’t been touched in a year. Something like this is going to be well-instrumented and alarmed, and it’s not going to generate customer success challenges. However, that level of maturity isn’t going to happen in a worthwhile timeframe under a single caregiver.

Make a list, check it twice

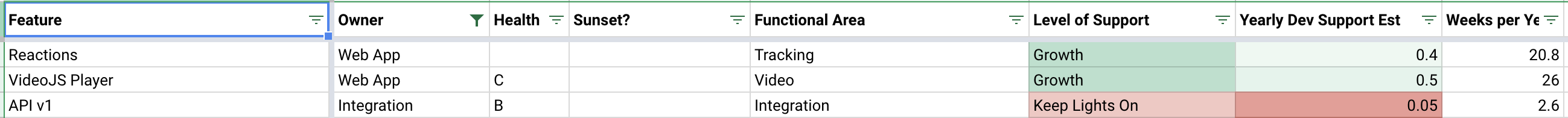

Have a spreadsheet that maps out your organizations’ portfolio: the applications, major features and subsystems and the wellness thereof. Who knows these systems? What’s the future interest in developing them? What should be actively sunset? Estimate the commitment it would take to give the care you want these systems to have.

You’re going to be short of what you want, nobody ever gets ahead of the list. The question is are you putting resources where you expect to be growing the business? How many C-grade features do you have in the field that are a drag to support and make the staff cringe? Are you understaffed 15% of where you’d like to be or 40%? What’s going to give? Have that conversation with the larger organization. Suggest specific changes: cuts, simplifications, pesky-time-stealers.

Do the right thing

Stop and plan. The allure of another quick-hit major feature delivered by a stellar talent is too good to be true. Products need a diversity of supporting actors to thrive in the long term. Engineers need a breadth of challenge and opportunities to keep them interested, learning and happy. Don’t shy from the exploratory work, go and learn about where you want to venture. But, if you’re going to take something on, take it all the way on. Give it the team it needs.